Simulated Annealing and Smitten Ice Cream

I live in Oakland, about a mile away from a Smitten Ice Cream store. Their selling point is their super-fast liquid nitrogen made-to-order ice cream. They claim that the ice cream, which is turned solid from liquid in 90 seconds, is creamier than regular ice cream. The validity of the scientific basis of this claim, I can’t answer, but I can make a simple mathematical model, derived from physical principles, to simulate the comparison between Smitten-made ice cream and regular ice cream.

Introduction

Of course, I wasn’t really thinking about Smitten when I was learning this stuff (I prefer Curbside). I was looking for ways to optimize a pretty rough function that was not really suitable for any gradient techniques, and I wanted to do something a little more sophisticated than literally a random search over some portion of the parameter space (which ended up being the best option, I’ll post about this later). A friend told me about simulated annealing, which seemed right up my alley because I did a little statistical mechanics in grad school. It ended up not working really well for my problem, but I did find this topic interesting so I thought I’d write about it. My goal in this post is to explain a simple model for flash freezing using simulated annealing. I was inspired by the image on the Wikipedia page, which you should compare to the images in this post.

Particle Configurations

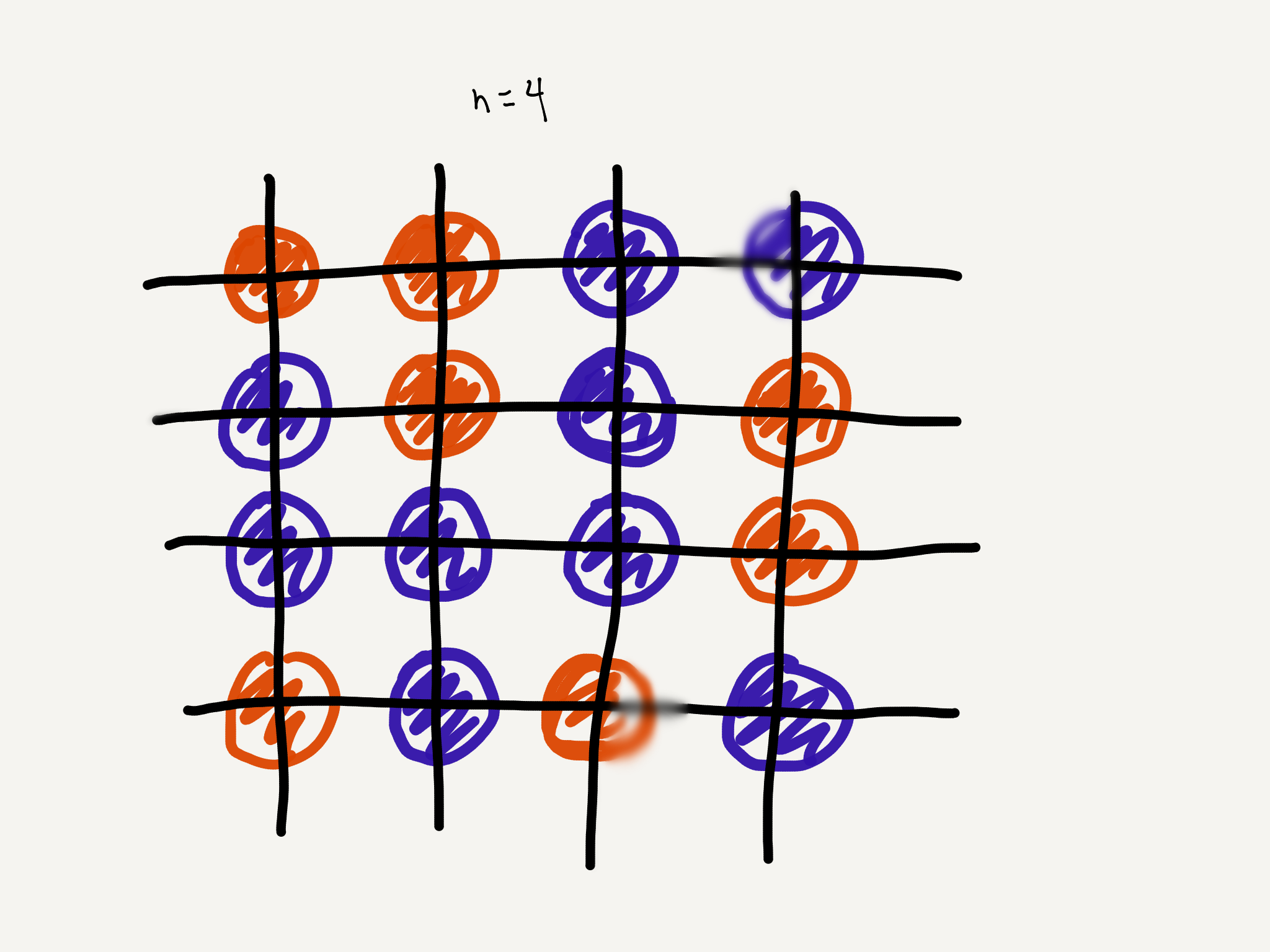

Let’s consider an arrangement of two types of particles in a box in a $n\times n$ two-dimensional lattice, like this:

Imagine that these particles form the liquid that Smitten ice cream is made from. Of course, the actual Smitten Goo in all probably has millions of different kinds of particles, not arranged in a grid, in three-dimensional space, whatever. Our purpose here is to simplify the very complicated reality of ice cream as much as we can until we arrive at the simplest model which demonstrates the essence of our question: creaminess.

To do this, we only need two types of particles. We’ll assign red particles to the value $+1$ and blue particles to the value $-1$. We will often say that red particles have positive spin and blue particles have negative spin.

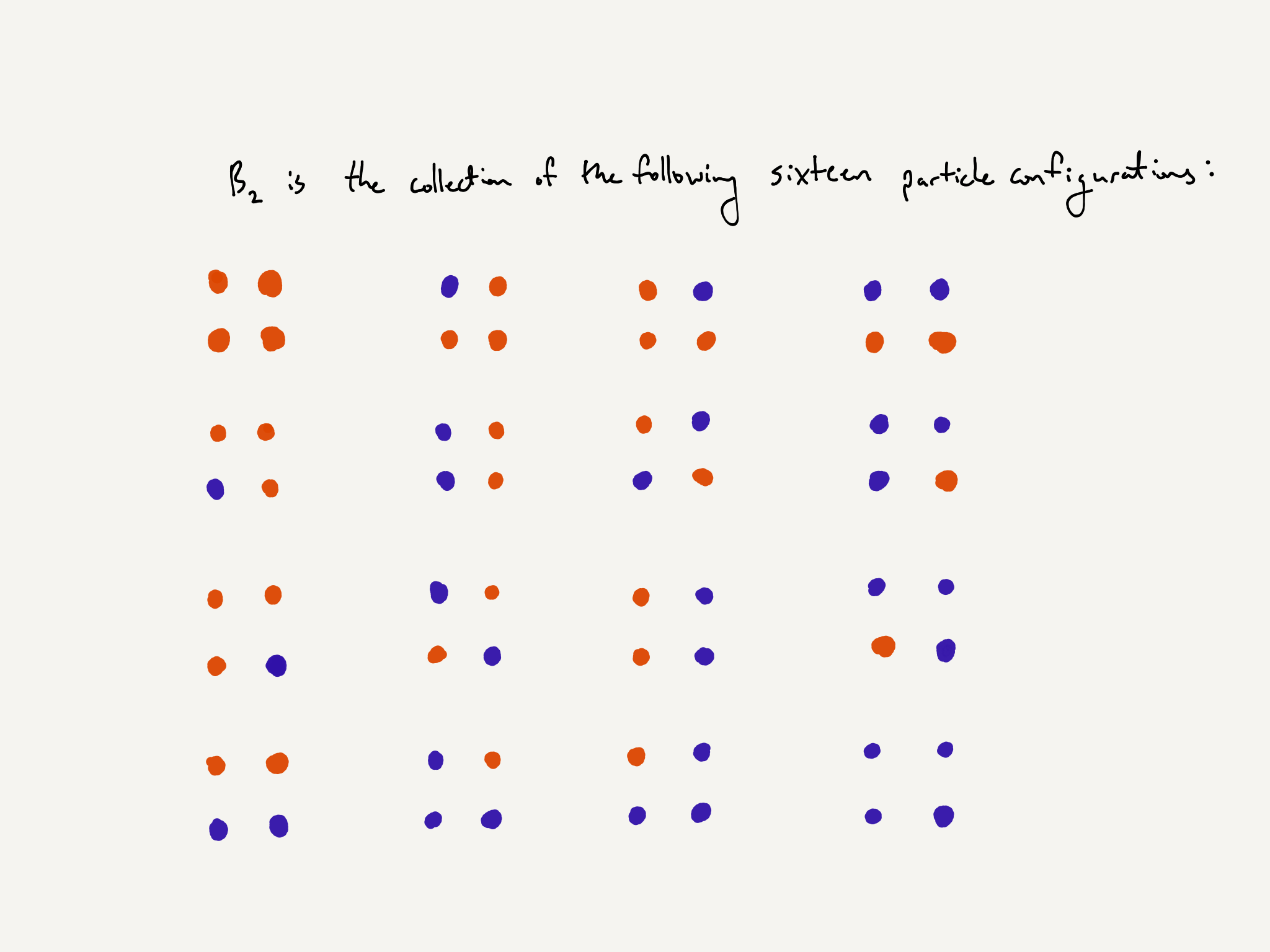

The entire arrangement of particles is called a particle configuration. To reiterate and simplify, a particle configuration consists of an assignment of $+1$ or $-1$ to each site in the $n\times n$ box. We will denote the collection of all particles configurations by $B_n$. So each element in $B_n$ is a different particle configuration.

Energy and temperature

Energy and temperature are two different quantities which work against, and for, one another to accomplish the task of freezing, whcih we are interested in because, remember, we love ice cream.

Energy

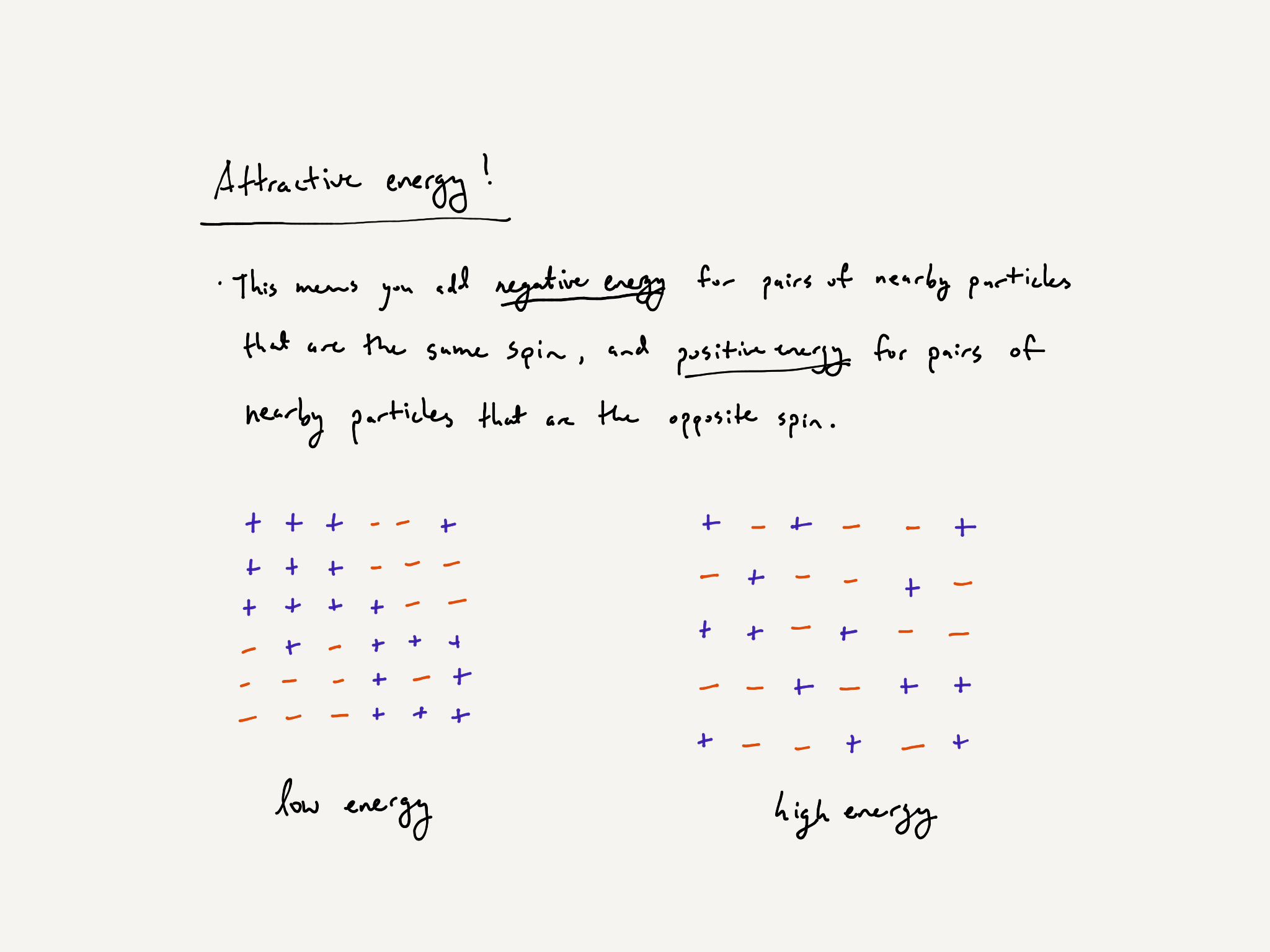

Here is the part where we invoke some physical principles. Each particle configuration has an energy associated to it. The details of energy are not pressing right now, so we will defer this discussion to the appendix. You can invent any notion of energy you’d like. We describe one type of energy, attractive energy, below.

Particles want to position themselves in a low-energy configuration. This is a general physical principle, the Second Law of Thermodynamics. In our model, their ability to do so depends on one parameter, temperature.

Temperature

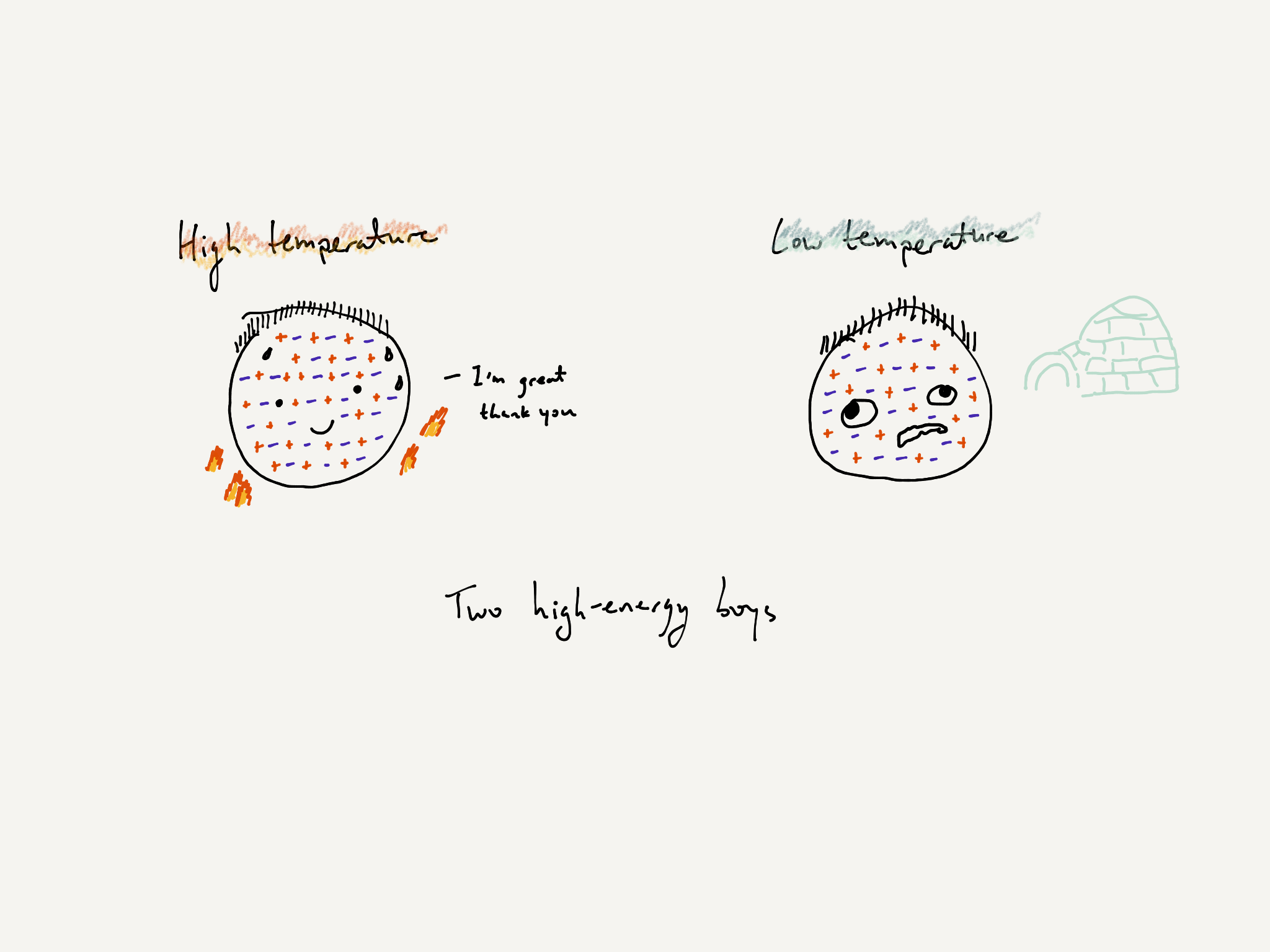

Here is another physically guided principle, though I’m not sure what the following tendency is called. At high temperatures, particles are more tolerant of high-energy configurations. As the temperature decreases, particles develop a more urgent need to have low energy.

The simulated annealing algorithm

So far, we have described what particles would like to do, but we haven’t specified a process with which they can accomplish their desires. We will begin to describe the simulated annealing algorithm, which does exactly this. Essentially, simulated annealing simulates the movement of particles in the process of freezing.

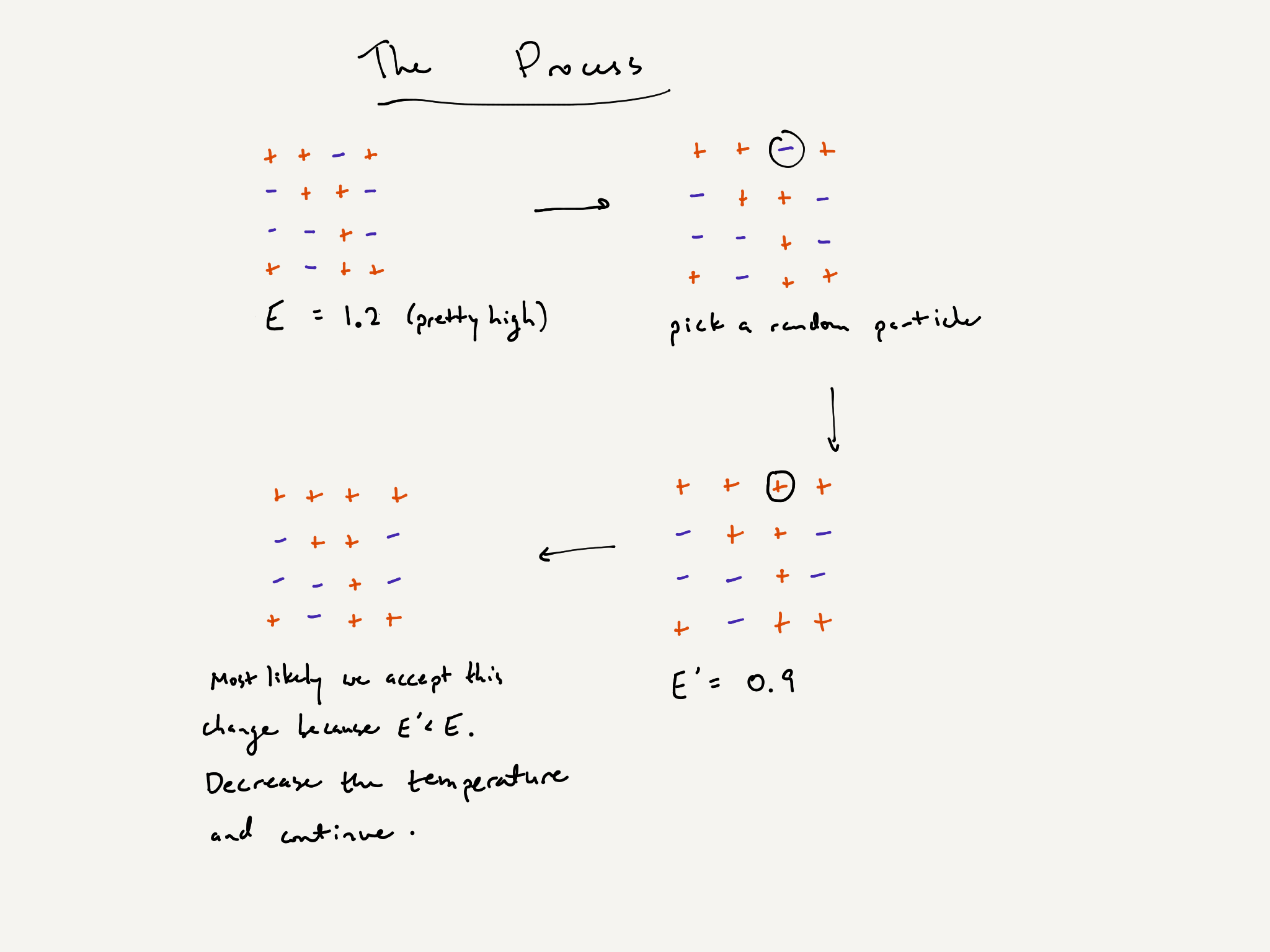

To simulate the process of freezing, we let a particle configuration evolve over time in the following way. At each time interval, one particle is randomly chosen. Then it either switches its spin or keeps its spin, depending on the energy of the configuration and the temperature of the environment.

Here is the qualitative evolution rule:

- Begin with a random initial configuration.

- Record the energy $E$.

- At each time interval, choose a random particle, switch its spin, and recompute the energy $E’$.

-

The particle configuration either accepts or declines the change. The choice is random, with tendencies listed below.

high temperature low temperature $E>E’$ slight inclination to accept strong inclination to accept $E<E’$ slight inclination to decline strong inclination to decline - Once the change is either accepted or declined, the temperature decreases by some amount.

- Repeat steps 2 through 5 for a fixed number of iterations.

This is not the exact physical process by which freezing of liquids happens. This is just a simple mathematical model which captures the creaminess property that we wish to investigate. This is the simulated annealing algorithm. It was invented for the sake of finding global extrema of a general class of functions. But that’s not what we’re using it for today.

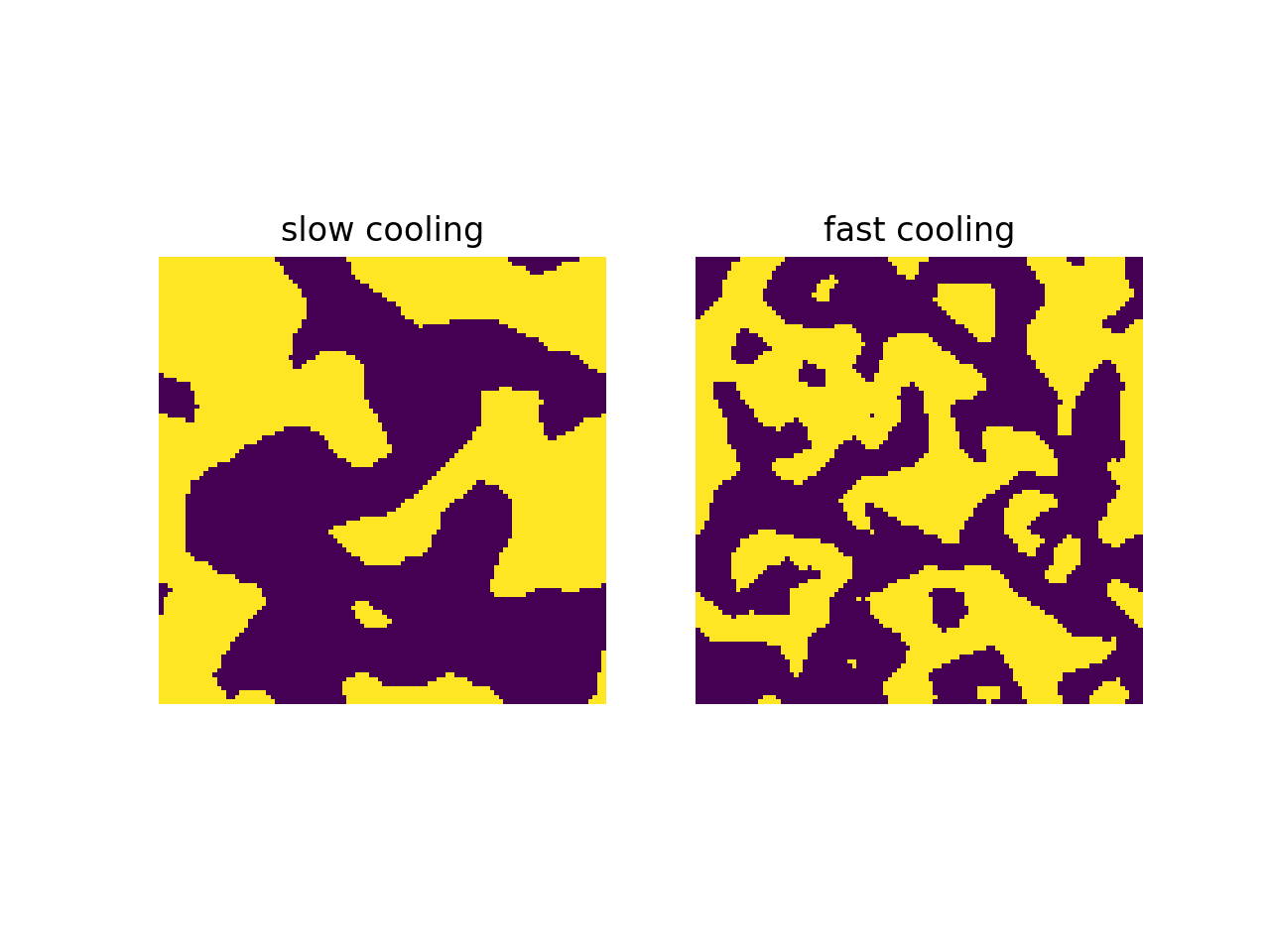

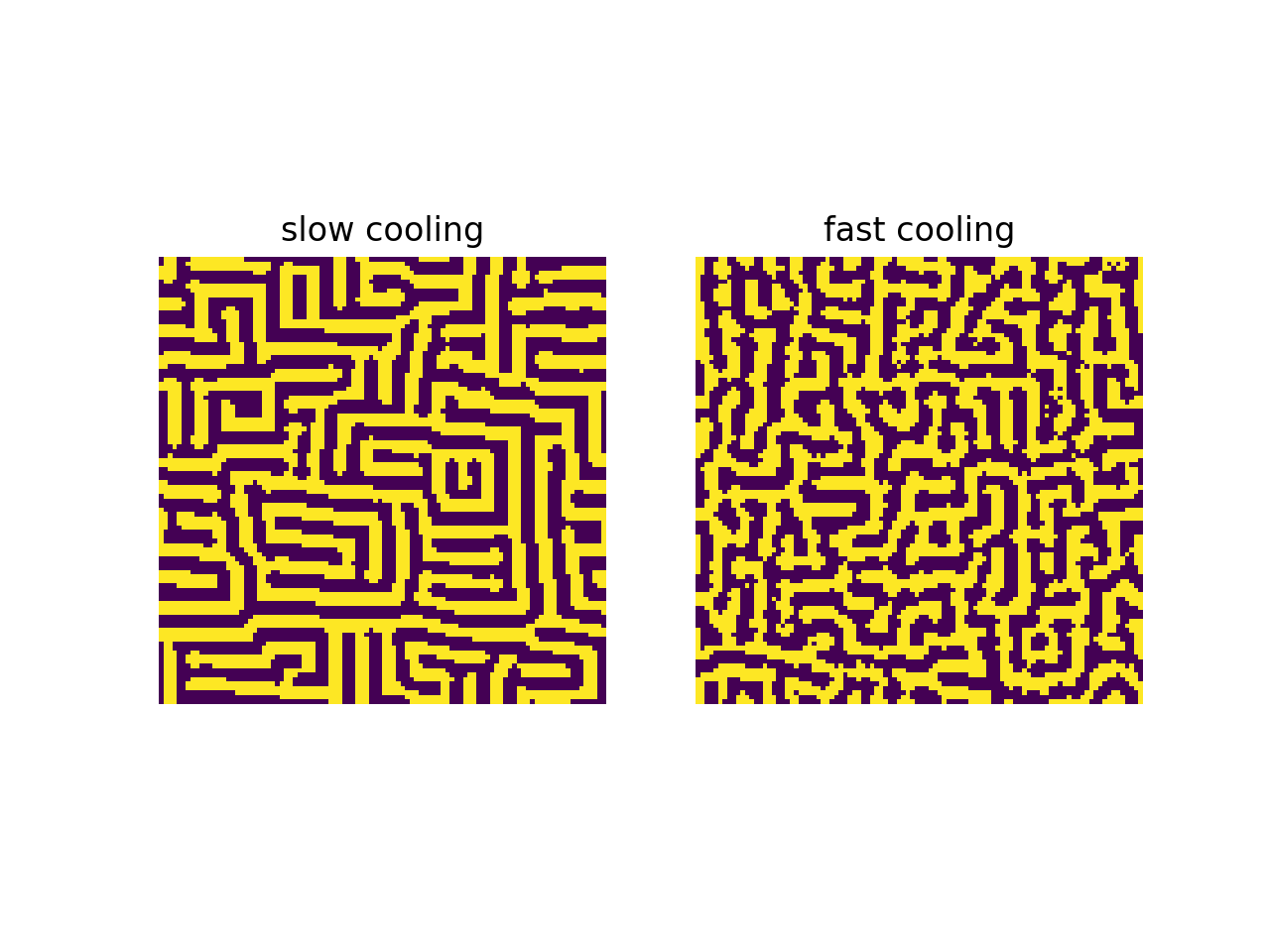

Flash Freezing

Here’s the interesting part. The speed of temperature decrease affects the microscopic structure of the particle configuration. If we compare two simulated annealing processes with different temperature decrease speeds and identical initial configurations, initial temperatures, final temperatures, and number of iterations, then the slow-cooled configuration will have more ‘‘order’’ than the fast-cooled configuration. We will see different examples of this phenomenon below. Below, we see slow-cooled configurations and fast-cooled configurations with identical parameters otherwise, for two different notions of energy.

In the first example, slow cooling results in larger groups of same-spin particles than fast cooling does. In the second example, slow cooling results in a more crystalline arrangement of particles than fast cooling does. This is what I mean when I say that slow cooling produces more order than fast cooling. The reason is that generally, more order means less energy, and slow cooling results in a lower final energy than fast cooling does. (When using simulated annealing for an optimization problem, fast cooling will find a local minimum close to the starting point, and slow cooling will get you closer to the global minimum.)

Conclusion

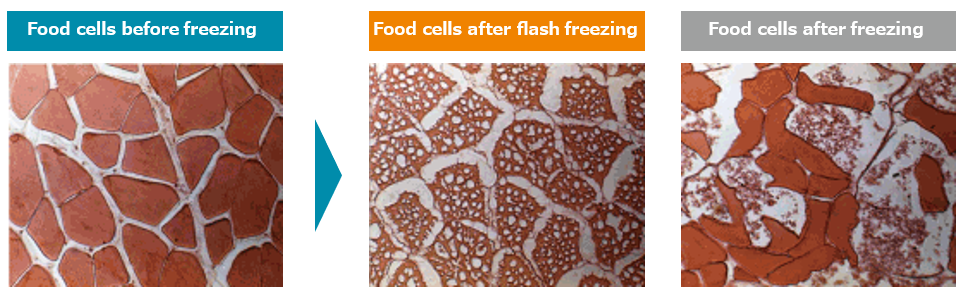

The freezing of ice cream is a much more complicated physical process than the simple model described above. However, this simple model captures many aspects of the ice cream freezing process. In particular, we see that a slow freezing process results in a crystalline structure while a fast freezing process results in a disordered liquidlike structure. Ice crystal formation follows a similar energy principle to the one described above, and fast freezing an ice cream goo is sure to generate smaller crystals, which are more disorderly, than slow freezing. See the image below to see what flash freezing does to food (?) cells (obtained from flash-freeze.net):

The flash-frozen cells retain cell structure because the ice crystals are smaller and less crystalline, which results in a smaller volume expansion (remember that ice is less dense than water), which prevents cells from exploding. Overall, flash-freezing a liquid keeps it more similar to the original liquid than slow-freezing it does. So there is a mathematical basis to Smitten’s claim that their 90-second liquid-nitrogen-induced ice cream making process produces smaller ice crystals and therefore a creamier texture than other ice creams.

To be clear, though, I don’t really detect any creaminess difference between Smitten and other ice creams. Especially when a Smitten pint is eleven dollars…

Appendix

I considered periodic grids, so that neighbors are easy to calculate. The energy I used for the first simulation above is a standard Ising model energy ++ E(x) = -\sum_{\|i-j\|_{\infty} = 1} x_i x_j ++ where

- $i,j \in \mathbb{Z}^2$;

- $x_i \in \{+1,-1\}$ is the spin at site $i$; and

- $\|i-j\|_{\infty}$ is the larger of the vertical and horizontal distances between $i$ and $j$.

The energy I used for the second simulation includes a repulsive energy at larger distances

++ E(x) = -\sum_{\|i-j\|_{\infty} = 1} x_i x_j + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{\|i-j\|_\infty=3} x_i x_j. ++

The temperature decrease speed I used was of the following shape, with speed parameter $\alpha$ ++ T(\alpha, t) = 4(1-t)^\alpha + 1, ++ where $t$ goes from zero to one. The slow cooling implemented a linear decrease with $\alpha=1$ and the parameter for fast cooling was $\alpha = 10$.

A few more details:

- the energies you should normalize by dividing by the size of the grid;

- the images are 100 by 100;

- the first pair of images went through 300000 time steps and the second pair through 100000 time steps;

- this takes impossibly long if you recalculate the entire energy after a sign flip, so you have to calculate the local change to update the energy;

- the switch-acceptance probability was ++ P(E, E’, T) = \frac{1}{Z}\exp((E - E’)/ T), ++ where $E$ is old energy, $E’$ is new energy, $T\in [0,1]$ is temperature, and $Z$ is a normalizing constant which I set to be one. Note that this quantity, though it is called a probability, is not exactly a probability because it may be larger than one. Just cut it off at one.